When the Equity Premium Fades, Alpha Shines

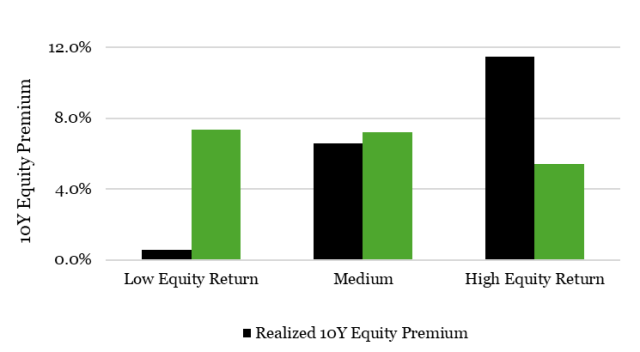

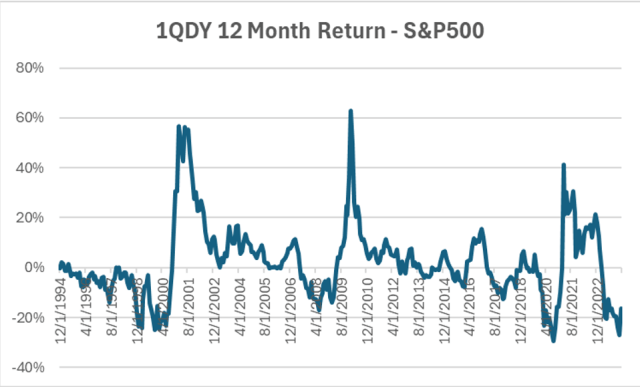

For more than a century, the equity risk premium (ERP) — the excess return from stocks over bonds or cash — has been the backbone of investing, delivering 5% to 6% annually above safer assets. But this era may be fading. With US valuations at historic highs, earnings growth slowing, and structural challenges mounting, the ERP could shrink to zero. In this new landscape, alpha — returns driven by skill and strategy — will become the primary source of performance. This blog examines why the ERP is declining, how alpha thrives in low-return environments, and most importantly how investors can adapt to a beta-constrained future. The Shrinking Equity Risk Premium Historically, US equities have returned 10% annually, fueled by expanding valuation multiples, robust earnings, favorable demographics, and US market dominance. From 1926 to 2024, the ERP averaged 6.2%, peaking at 10.6% from 2015 to 2024. Yet, history reveals a pattern of mean reversion: strong decades often precede weaker ones. After high-return periods, the subsequent decade’s ERP typically underperforms the long-term average by ~1%, while weak decades lead to returns ~1% above average (Figure 1). Figure 1 | Realized and subsequent US 10-year equity premiums Source: Robeco and Kenneth French Data library. US stock market returns 1926-2024. This graph is for illustrative purposes only. Today’s market conditions raise red flags. The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio hovers near historic highs, dividend yields are subdued, and real earnings growth faces headwinds from aging populations and rising costs. Leading asset managers, including AQR, Research Affiliates, Robeco, and Vanguard, project a near-zero US ERP for 2025 to 2029, with valuation-based models even warning of negative returns. In contrast, global markets –particularly Europe and emerging markets — offer a more attractive and still positive ERP, driven by higher valuations and growth potential. Alpha’s Rising Importance As beta weakens, alpha takes the spotlight. Factor premiums — returns from strategies like value, momentum, quality, and low volatility — perform robustly in low-return environments. Historical data (1926 to 2024) shows that when equity returns are high, factor alpha contributes 25% of total returns (3.9% of 15.4%). In weak markets, alpha’s share soars to 89% (4.9% of 5.5%), as factor premiums remain stable or rise (Figure 2). Figure 2 | Realized US Equity and Factor Premiums Source: Robeco and Kenneth French Data library. Sample US 1926-2024.This graph is for illustrative purposes only. Figure 2 demonstrates that factor premiums grow in importance as equity returns decline, boosting alpha’s role. Academic research reinforces this dynamic. Kosowski (2011) found that mutual funds generate +4.1% alpha during recessions, when markets are toughest, compared to -1.3% in expansions. Blitz (2023) shows that factor alphas increase when equity returns fall, making strategies like value and momentum critical in low-ERP environments. A broader historical perspective (1870 to 2024) by Baltussen, Swinkels, and van Vliet (2023) confirms that factor premiums thrive across market cycles, particularly during high-inflation or low-growth periods. Low-volatility stocks, for instance, outperform during market downturns, offering a defensive edge. This shift has profound implications. In a zero-ERP world, alpha isn’t just an enhancement; it is the dominant source of return. Active quantitative strategies, which systematically exploit factors like quality or low volatility, can deliver consistent outperformance when market beta falters. For investors accustomed to passive investing, this marks a paradigm shift toward skill-based approaches. Investing in a Low-ERP World A shrinking ERP requires investors to rethink their approach. Traditional market exposure, once the primary return driver, may no longer deliver. Instead, investors should prioritize alpha through systematic, evidence-based strategies: Factor Investing: Diversified exposure to factors like value, momentum, and low volatility can generate reliable alpha. Defensive equities, which tend to outperform in downturns, provide a cushion in volatile or sideways markets. Low-volatility strategies, for example, have historically delivered higher risk-adjusted returns during low-growth periods. Global Diversification: With Europe and emerging markets offering higher ERPs (still positive vs. the US’s near-zero), reallocating capital abroad can enhance returns. Small caps and equal-weighted strategies, often overlooked in favor of large-cap growth, also show promise due to their attractive valuations. Active Management: High-active-share or long-short strategies can capitalize on market inefficiencies, particularly in undervalued segments like small caps or low-volatility stocks. Active quant approaches, blending factor exposures with disciplined risk management, are well-suited to a low-ERP environment. A low-ERP world could reshape market dynamics. As investors chase alpha, capital may flow into factor-based strategies, potentially elevating valuations for these assets. The US’s market dominance, fueled by a high ERP over the past decade, may weaken as capital shifts to Europe, Asia, or small-cap markets. This could reverse the multi-decade trend toward passive investing, rewarding managers with proven alpha-generating skills. Moreover, a prolonged low-ERP environment may amplify the appeal of defensive strategies. Low-volatility and low-beta factors, which thrive in uncertainty, could attract significant inflows, offering stability in a market where positive returns are scarce. Investors who adapt early by embracing active quant strategies or diversifying globally stand to gain a competitive edge. Key Takeaway A declining ERP does not signal the end of investing; it demands a pivot to alpha-driven strategies. With US equity returns under pressure, systematic approaches like factor investing, defensive equities, and global diversification offer a path to resilient performance. In a zero-ERP world, alpha is not just a bonus; it’s the key to capital growth. As beta fades, alpha shines. For a deeper dive, read my full report. Pim van Vliet, PhD, is the author of High Returns from Low Risk: A Remarkable Stock Market Paradox, with Jan de Koning. Link to research papers by Pim van Vliet. References AQR. (2025). “2025 Capital market assumptions for major asset classes.” Available at www.aqr.com. Baltussen, G., Swinkels, L., & van Vliet, P. (2023). “Investing in deflation, inflation, and stagflation regimes,” Financial Analysts Journal, 79(3), 5–32. Blitz, D. (2023). “The cross-section of factor returns,” The Journal of Portfolio Management, 50(3), 74–89. Fandetti, M. (2024). “CAPE is high: Should you care?” Enterprising Investor. Available at www.cfainstitute.org. GMO. (2024). “Record highs…but we’re still excited.” Available at www.gmo.com. Kosowski, R. (2011).

When the Equity Premium Fades, Alpha Shines Read More »