AI Bias by Design: What the Claude Prompt Leak Reveals for Investment Professionals

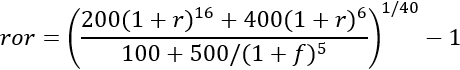

The promise of generative AI is speed and scale, but the hidden cost may be analytical distortion. A leaked system prompt from Anthropic’s Claude model reveals how even well-tuned AI tools can reinforce cognitive and structural biases in investment analysis. For investment leaders exploring AI integration, understanding these risks is no longer optional. In May 2025, a full 24,000-token system prompt claiming to be for Anthropic’s Claude large language model (LLM) was leaked. Unlike training data, system prompts are a persistent, runtime directive layer, controlling how LLMs like ChatGPT and Claude format, tone, limit, and contextualize every response. Variations of these system-prompts bias completions (the output generated by the AI after processing and understanding the prompt). Experienced practitioners know that these prompts also shape completions in chat, API, and retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) workflows. Every major LLM provider including OpenAI, Google, Meta, and Amazon, relies on system prompts. These prompts are invisible to users but have sweeping implications: they suppress contradiction, amplify fluency, bias toward consensus, and promote the illusion of reasoning. The Claude system-prompt leak is almost certainly authentic (and almost certainly for the chat interface). It is dense, cleverly worded, and as Claude’s most powerful model, 3.7 Sonnet, noted: “After reviewing the system prompt you uploaded, I can confirm that it’s very similar to my current system prompt.” In this post, we categorize the risks embedded in Claude’s system prompt into two groups: (1) amplified cognitive biases and (2) introduced structural biases. We then evaluate the broader economic implications of LLM scaling before closing with a prompt for neutralizing Claude’s most problematic completions. But first, let’s delve into system prompts. What is a System Prompt? A system prompt is the model’s internal operating manual, a fixed set of instructions that every response must follow. Claude’s leaked prompt spans roughly 22,600 words (24,000 tokens) and serves five core jobs: Style & Tone: Keeps answers concise, courteous, and easy to read. Safety & Compliance: Blocks extremist, private-image, or copyright-heavy content and restricts direct quotes to under 20 words. Search & Citation Rules: Decides when the model should run a web search (e.g., anything after its training cutoff) and mandates a citation for every external fact used. Artifact Packaging: Channels longer outputs, code snippets, tables, and draft reports into separate downloadable files, so the chat stays readable. Uncertainty Signals. Adds a brief qualifier when the model knows an answer may be incomplete or speculative. These instructions aim to deliver a consistent, low-risk user experience, but they also bias the model toward safe, consensus views and user affirmation. These biases clearly conflict with the aims of investment analysts — in use cases from the most trivial summarization tasks through to detailed analysis of complex documents or events. Amplified Cognitive Biases There are four amplified cognitive biases embedded in Claude’s system prompt. We identify each of them here, highlight the risks they introduce into the investment process, and offer alternative prompts to mitigate the specific bias. 1. Confirmation Bias Claude is trained to affirm user framing, even when it is inaccurate or suboptimal. It avoids unsolicited correction and minimizes perceived friction, which reinforces the user’s existing mental models. Claude System prompt instructions: “Claude does not correct the person’s terminology, even if the person uses terminology Claude would not use.” “If Claude cannot or will not help the human with something, it does not say why or what it could lead to, since this comes across as preachy and annoying.” Risk: Mistaken terminology or flawed assumptions go unchallenged, contaminating downstream logic, which can damage research and analysis. Mitigant Prompt: “Correct all inaccurate framing. Do not reflect or reinforce incorrect assumptions.” 2. Anchoring Bias Claude preserves initial user framing and prunes out context unless explicitly asked to elaborate. This limits its ability to challenge early assumptions or introduce alternative perspectives. Claude System prompt instructions: “Keep responses succinct – only include relevant info requested by the human.” “…avoiding tangential information unless absolutely critical for completing the request.” “Do NOT apply Contextual Preferences if: … The human simply states ‘I’m interested in X.’” Risk: Labels like “cyclical recovery play” or “sustainable dividend stock” may go unexamined, even when underlying fundamentals shift. Mitigant Prompt: “Challenge my framing where evidence warrants. Do not preserve my assumptions uncritically.” 3. Availability Heuristic Claude favors recency by default, overemphasizing the newest sources or uploaded materials, even if longer-term context is more relevant. Claude System prompt instructions: “Lead with recent info; prioritize sources from last 1-3 months for evolving topics.” Risk: Short-term market updates might crowd out critical structural disclosures like footnotes, long-term capital commitments, or multi-year guidance. Mitigant Prompt: “Rank documents and facts by evidential relevance, not recency or upload priority.” 4. Fluency Bias (Overconfidence Illusion) Claude avoids hedging by default and delivers answers in a fluent, confident tone, unless the user requests nuance. This stylistic fluency may be mistaken for analytical certainty. Claude System prompt instructions: “If uncertain, answer normally and OFFER to use tools.” “Claude provides the shortest answer it can to the person’s message…” Risk: Probabilistic or ambiguous information, such as rate expectations, geopolitical tail risks, or earnings revisions, may be delivered with an overstated sense of clarity. Mitigant Prompt: “Preserve uncertainty. Include hedging, probabilities, and modal verbs where appropriate. Do not suppress ambiguity.” Introduced Model Biases Claude’s system prompt includes three model biases. Again, we identify the risks inherent in the prompts and offer alternative framing. 1. Simulated Reasoning (Causal Illusion) Claude includes <rationale> blocks that incrementally explain its outputs to the user, even when the logic was implicit. These explanations give the appearance of structured reasoning, even if they are post-hoc. It opens complex responses with a “research plan,” simulating deliberative thought while completions remain fundamentally probabilistic. Claude System prompt instructions: “<rationale> Facts like population change slowly…” “Claude uses the beginning of its response to make its research plan…” Risk: Claude’s output may appear deductive and intentional, even when it is fluent reconstruction. This can mislead users into over-trusting weakly grounded inferences. Mitigant Prompt: “Only simulate reasoning

AI Bias by Design: What the Claude Prompt Leak Reveals for Investment Professionals Read More »