Commodities for the Long Run?

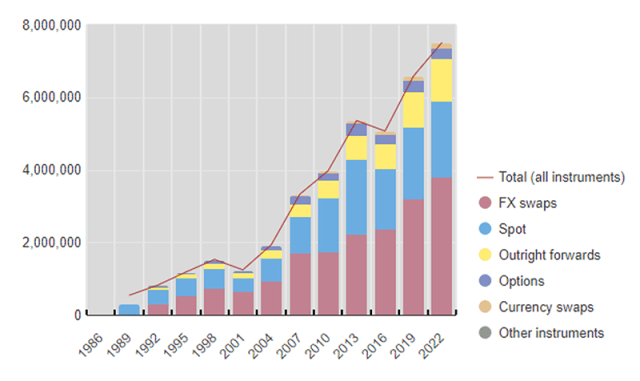

If you focus only on returns and covariances over a one-year investment horizon, you may conclude that commodities have no place in an investment portfolio. The efficiency of commodities improves dramatically over longer investment horizons, however, especially when using expected returns and maintaining historical serial dependencies. We’ll demonstrate how allocations to commodities can change across investment horizon, especially when considering inflation. Our analysis suggests that investment professionals may need to take a more nuanced view of certain investments, especially real assets like commodities, when building portfolios. This is the third in a series of posts about our CFA Institute Research Foundation paper. First, we demonstrated that serial correlation is present in various asset classes historically. Second, we discussed how the risk of equities can change according to investment horizon. Historical Inefficiency of Commodities Real assets such as commodities are often viewed as being inefficient within a larger opportunity set of choices and therefore commonly receive little (or no) allocation in common portfolio optimization routines like mean variance optimization (MVO). The historical inefficiency of commodities is documented in Exhibit 1, which includes the historical annualized returns for US cash, US bonds, US equities, and commodities from 1870 to 2023. The primary returns for US cash, US bonds, and US equities were obtained from the Jordà-Schularick-Taylor (JST) Macrohistory Database from 1872 (the earliest year the complete dataset is available) to 2020 (the last year available). We used the Ibbotson SBBI series for returns thereafter. The commodity return series uses returns from Bank of Canada Commodity Price Index (BCPI) from 1872 to 1969 and the S&P GSCI Index from 1970 to 2023. The BCPI is a chain Fisher price index of the spot or transaction prices in US dollars of 26 commodities produced in Canada and sold in world markets. The GSCI — the first major investable commodity index — is broad-based and production weighted to represent the global commodity market beta. We selected the GSCI due to its long history, similar component weights to the BCPI, and the fact that there are several publicly available investment products that can be used to roughly track its performance. These include the iShares exchange traded fund (ETF) GSG, which has an inception date of July 10, 2006. We used the two commodity index proxies primarily because of data availability (e.g., returns going back to 1872) and familiarity. The results from the analysis should be viewed with these limitations in mind. Exhibit 1. Historical Standard Deviation and Geometric Returns for Asset Classes: 1872-2023. Source: Jordà-Schularick-Taylor (JST) Macrohistory Database. Bank of Canada. Morningstar Direct. Authors’ calculations. Commodities appear to be incredibly inefficient when compared to bills, bonds, and equities. For example, commodities have a lower return than bills or bonds, but significantly more risk. Alternatively, commodities have the same approximate annual standard deviation as equities, but the return is approximately 600 basis points (bps) lower. Based entirely on these values, allocations to commodities would be low in most optimization frameworks. What this perspective ignores, though, is the potential long-term benefits of owning commodities, especially during periods of higher inflation. Exhibit 2 includes information about the average returns for bills, bonds, equities, and commodities, during different inflationary environments. Exhibit 2. Average Return for Asset Classes in Different Inflationary Environments: 1872-2023. Source: Jordà-Schularick-Taylor (JST) Macrohistory Database. Bank of Canada. Morningstar Direct. Authors’ calculations. Data as of December 31, 2023. We can see that while commodities have had low returns when inflation is low, they have outperformed dramatically when inflation is high. The correlation of commodities to inflation increases notably over longer investment horizons, increasing from approximately 0.2 for one-year periods to 0.6 for 10-year periods. In contrast, the correlation of equities to inflation is only approximately -0.1 for one-year periods and approximately 0.2 for 10-year periods. In other words, focusing on the longer-term benefits of owning commodities and explicitly considering inflation could dramatically change the perceived efficiency in a portfolio optimization routine. Listen to my conversation with Mike Wallberg, CFA: Allocating to Commodities While inflation can be explicitly considered in certain types of optimizations, such as “surplus” or liability-relative optimizations, one potential issue with these models is that changes in the prices of goods or services do not necessarily move in sync with the changes in financial markets. There could be lagged effects. For example, while financial markets can experience sudden changes in value, inflation tends to take on more of a latent effect: changes can be delayed and take years to manifest. Focusing on the correlation (or covariance) of inflation with a given asset class like equities over one-year periods (e.g., calendar years) may hide potential longer-term benefits. To determine how optimal allocations to commodities would have varied by investment horizon, we performed a series of portfolio optimizations for one- to 10-year investment horizons, in one-year increments. Optimal allocations were determined using a Constant Relative Risk Aversion (CRRA), which adjusts for risk the cumulative growth in wealth over a given investment horizon. Optimal allocations corresponding to equity allocations from 5% to 100%, in 5% increments, were determined based on target risk aversion levels. We included four asset classes in the portfolio optimizations: bills, bonds, equities, and commodities. Exhibit 3 includes the optimal allocations to commodities for each of the scenarios considered. Exhibit 3. Optimal Allocation to Commodities by Wealth Definition, Equity Risk Target, and Investment Period: 1872-2023. The allocation to commodities remained at approximately zero for virtually all equity allocation targets when wealth was defined in nominal returns (Panel A). On the other hand, when wealth was defined in real terms (i.e., including inflation), the allocations proved to be relatively significant over longer investment periods (Panel B). That was especially true for investors targeting moderately conservative portfolios (e.g., ~40% equity allocations), where optimal allocations to commodities would be roughly 20%. In other words, the perceived historical benefits of allocating to commodities have varied significantly depending on the definition of wealth (nominal versus real) and the assumed investment period (e.g., moving from one year to 10 years). Forward-looking expectations for

Commodities for the Long Run? Read More »