Managing Regret Risk: The Role of Asset Allocation

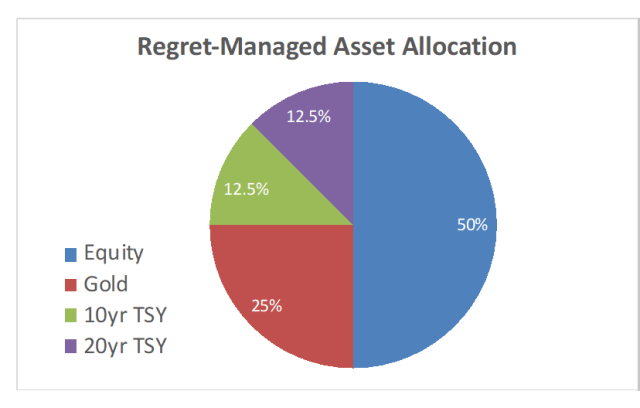

Traditional investment approaches assume investors have equal access to market information and make rational, emotionless decisions. Behavioral finance, championed by Richard Thaler, Daniel Kahneman, and Amos Tversky, challenges this assumption by recognizing the role emotions play. But the ability to quantify and manage these emotions eludes many investors. They struggle to maintain their investment exposures through the ups and downs of market cycles. In this post, I introduce a holistic asset allocation process intended to manage the phenomenon of regret risk by considering each client’s willingness to maintain an investment strategy through market cycles. I also evaluate the suitability of a client’s expectations to determine if a strategy is a good match and is likely to be sustained. The upshot is a case for equally weighted investment strategies. The Importance of Maintaining an Investment Strategy Investors must maintain their strategy over a long period of time if they are to achieve the expected results. This requires rebalancing their portfolios periodically to maintain exposure in each segment of the strategy, especially across periods of high volatility. Investors whose emotions lead them to deviate from the strategy are effectively timing the market by making predictions about future returns. These actions present their own form of risk, adding to the existing risk of unpredictable markets. The Role of Knowledge We must acknowledge that we can’t predict the future with any certainty. Despite having data, analysis, and expert opinions, our forward-looking decisions are educated guesses. To manage the uncertainty of this knowledge gap, we must plan for the outcomes that may occur by holding investments that capitalize on favorable outcomes, combining these with other investments that mitigate the unfavorable ones. The investor can reasonably expect more stable returns from this more intuitive diversification approach. I evaluated my results using nearly a century of market data that cover the US economy across many of its market cycles and through times of both peace and extreme geopolitical stress. This analysis includes the types of regret-inducing events investors are likely to encounter. The Nature of Regret Regret is an emotional reaction to extreme events, whether the events produce losses or gains. When regret drives an investor to abandon an investment strategy, this adds the risk of a whipsaw effect: being wrong on both the exit from and re-entry into the investment markets. Over the past 95 years, the S&P 500 has returned 9.6% annually. Missing out on the 10 best years would have lowered that return to only 6%. However, avoiding the worst 10 years would have boosted the return to 13.4%. The investment markets provide ample opportunities for regret. This makes guarding against regret critical to helping investors maintain their investment strategies. Asset Allocation Through the Lens of Regret Harry Markowitz is called the father of Modern Portfolio Theory for his work in quantifying the benefits of diversification. Yet, in his own portfolio he divided his money equally between stocks and bonds, since he did not know which was likely to do better in any given year. This demonstrates the wisdom of splitting assets equally across investments. The case for equally weighted strategies is based on avoiding risk concentrations and equalizing each asset’s marginal contribution to return and risk. This is a fundamental driver of efficiency. We see many examples of equally weighted indexes outperforming their capitalization-weighted counterparts. We used a 70/30 mix of large-cap and small-cap stocks for the US equity market, and a 50/50 mix of 10-year and 20-year Treasuries for the bond market. We expect these investments to have complementary, if not opposite reactions to market conditions, making them ideal diversifiers. We also prepared for a third scenario — the most stressful and regret-inducing — the likelihood of intense geopolitical turmoil. When markets become unsettled, economies are distressed, and currencies lose much of their value. During these times, investors turn to real assets as a more secure store of wealth and liquidity. We created a category of reserves comprising gold and Treasury bonds. Following our naïve diversification approach, we split the reserves allocation equally between bonds and gold. Figure 1: Regret-managed strategy Evaluating the Diversification of the Regret-Managed Strategy Over 95 Years We found that equities, bonds, and reserves were uncorrelated with each other. Within reserves, the gold and Treasuries were also uncorrelated to each other. While gold and Treasuries earned the same return, their combination earned a significantly higher return. Table 1: Correlation of assets within regret-managed portfolio Figure 2: Growth of reserves portfolio Performance Results Our goal was to minimize regret and the likelihood of abandoning the asset allocation. I found that the regret-managed portfolio performed well in the context of traditional efficiency. The portfolio return is higher than the average of its components, and its risk is nearly as low as its lower-volatility reserves. Table 2: Returns over 95 years Figure 3: Efficiency of regret-managed strategy Regret-Managed Strategy Versus Classic 60-40 Benchmark The regret-managed strategy outperformed the familiar 60-40 benchmark (S&P 500 + Aggregate bonds) since the benchmark’s inception nearly 50 years ago. This shows that my efforts to minimize regret did not come at the cost of efficiency. The 60-40 investor also experienced greater severity and frequency of regret. Figure 4: Regret-managed strategy vs 60-40 strategy Quantifying Regret The first step in measuring regret is to assign a limit to the returns that qualify as regret-inducing. Perceptions of regret are unique to each client, recognizing that investors respond more strongly to losses than to gains. Some suggest that the response to losses is twice that of similar-sized gains. We developed our upside and downside regret targets with negative values at about half the positive target. Our base case sets the targets at -12% and 25%. Any returns beyond this range are regret-inducing. The next step is to determine the magnitude and the likelihood of upside and downside regret experiences. We calculated the average of the returns exceeding the regret targets, along with their percentage occurrence. These produce an expected regret penalty in the same units as the expected

Managing Regret Risk: The Role of Asset Allocation Read More »