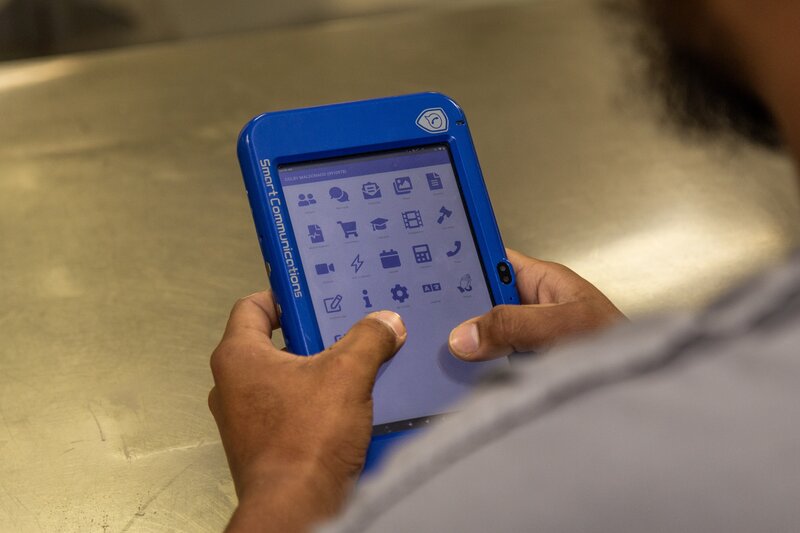

By Jack Karp | June 13, 2025, 7:00 PM EDT · Listen to article Your browser does not support the audio element. Corrections officials say that electronic tablets, like those available to inmates at the Tarrant County, Texas, Jail, let inmates keep in touch with loved ones and access more entertainment and education options, but the tablets’ critics say the tablets really help carceral facilities surveil prisoners while making money for the tablet providers. (Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office) Kenneth Roberts couldn’t hold his daughter’s drawings. Ruben Gonzalez-Magallanes couldn’t smell his mother’s perfume on her letters. Zachary Greenberg told his family to stop sending him mail entirely. That’s because San Mateo, California, jails, where the three men were incarcerated, barred inmates from receiving physical mail in 2021, and began scanning and digitizing that mail to be delivered via electronic tablets. The policy has been devastating to the inmates and their families, according to Stephanie Krent, a staff attorney at the Knight First Amendment Institute, which is representing several of those inmates and families in their free-speech challenge to San Mateo’s ban. “Mail can be incredibly important, especially in the context of a prison or a jail where there are already so few means of contact,” Krent told Law360. But jails are transforming mail from a physical object that an inmate can keep in their possession into a digital file that can be archived. “It creates a very different feeling knowing that your mail is living on for years and years and years, and long after you leave that facility people there can pull that letter up at any moment. That creates a chilling effect,” Krent said. Krent’s suit, which seeks to stop the county from digitizing inmates’ mail and order the delivery of physical mail restored, has moved into discovery — and isn’t the only pending suit challenging jails’ move to push more services onto digital tablets.

Tablets can also be used as an excuse to cancel in-person programming and classes, because, ‘Hey, it’s on your tablet now.’

Nila Bala

University of California at Davis School of Law

The children and parents of individuals incarcerated in two Michigan counties are suing jail officials there for allegedly banning in-person visits in exchange for a cut of the revenue private companies earn from video visits. A growing number of prisons and jails like those in San Mateo and Michigan are implementing such limits or even bans on physical mail and in-person visits, providing inmates with electronic tablets to read scanned mail and video-visit with loved ones instead. Corrections officials say the tablets keep drugs out of facilities, make it easier for inmates to connect with family, and offer access to far more books and entertainment options. But prisoner advocates warn that the technology makes it easier for inmates to be surveiled while cutting them further off from the outside world. And it ensures that prison telecom companies — and sometimes corrections departments — keep making money. “There do seem to be benefits to tablets. I wouldn’t advocate eliminating them altogether, especially because incarcerated individuals have expressed a desire to have and keep tablets,” said University of California at Davis School of Law professor Nila Bala. “On the flip side, tablets can also be used as an excuse to cancel in-person programming and classes, because, ‘Hey, it’s on your tablet now.’” “A Lifeline to the Outside World” The use of electronic tablets behind bars is skyrocketing. Just 12 state prison systems offered the tablets to inmates in 2019. By late 2024, at least 48 states were already employing or introducing the technology, with just two companies — Securus Technologies, which owns JPay Inc., and Global Tel*Link Corp., also known as ViaPath — contracted to provide and operate the tablets in most of those states, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

The tablets, which have fewer features than those consumers buy, let inmates communicate with friends and family via video and electronic messaging; access books, movies, games and podcasts; and take advantage of educational content and electronic law libraries. Some facilities also scan inmates’ physical mail, which can then only be read on the tablets. This digital shift has improved prison conditions, according to corrections officials. For starters, the technology has “most definitely” reduced the drugs and contraband being snuck into her jail via paper mail, said Shannon Herklotz, executive chief deputy in the Detention Bureau of the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office in Texas. Inmates at the Tarrant County Jail began receiving mail electronically via Smart Communications’ MailGuard system in 2024. The tablets’ video and instant messaging features also make it easier for inmates to stay in touch with loved ones, particularly those who can’t travel to the jail, Herklotz added. The tablets have similarly benefited inmates in Connecticut state facilities, who were given the tablets for free in 2020 and can make phone calls to preapproved phone numbers from the privacy of their own cells as a result, according to Connecticut Department of Correction Public Information Officer Andrius Banevicius. “Having the ability to communicate with family members has had an overall positive effect on the atmosphere of the facilities,” Banevicius said. The tablets aIso let incarcerated individuals access a much larger selection of entertainment and educational materials, including games, movies, books and podcasts, at least some of which are free, according to facility operators. Inmates in the Tarrant County Jail can read over 70,000 free books, according to Herklotz. Connecticut inmates’ tablets include free games, radio broadcasts, books and podcasts, according to Banevicius. Colorado inmates can access a free electronic law library and purchase ebooks, music and movies, according to Christian Andrade at the Colorado Department of Corrections, which began providing its inmates with tablets in 2024. “The decision to implement tablets was grounded in research showing that improved communication and access to meaningful programming can reduce recidivism, support rehabilitation and contribute to safer facilities,” Andrade said. Even experts who voice concerns about