Believing in Spirits and Life After Death Is Common Around the World

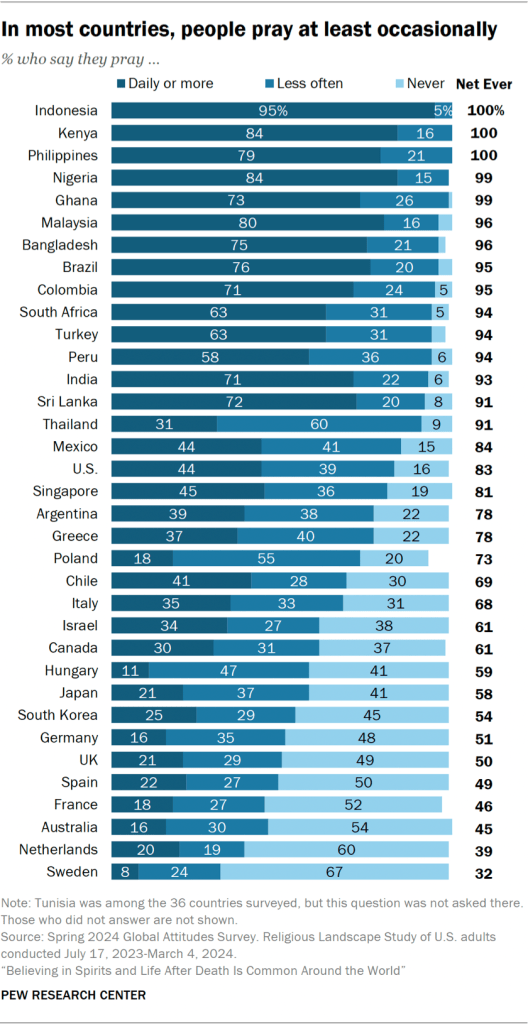

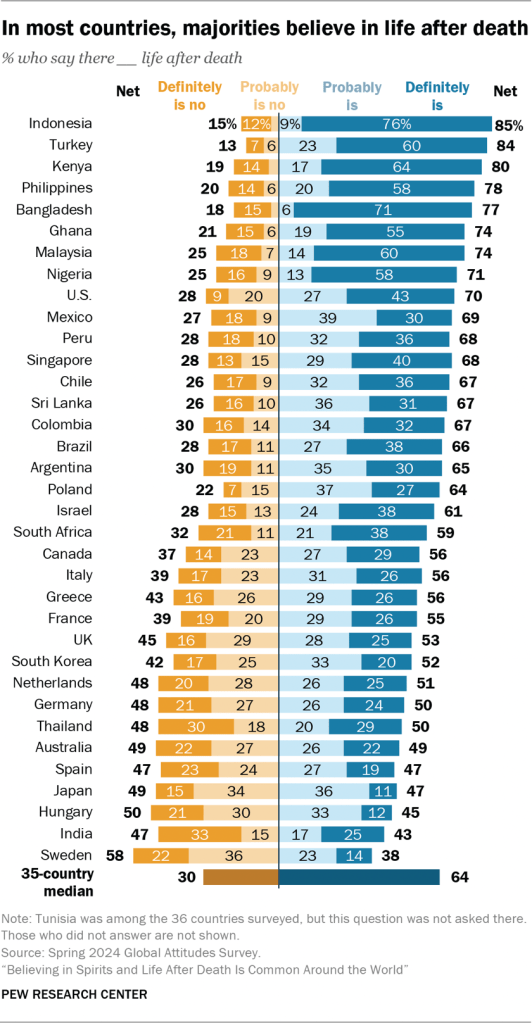

(Handini Atmodiwiryo/Getty Images) How we did this Pew Research Center conducted this survey to measure the prevalence of a variety of religious and spiritual beliefs and practices around the world. The survey included some questions grounded in the Christian, Jewish and Muslim traditions, as well as some questions with roots in Buddhism, Hinduism and other Asian faiths. We wanted to see how widely such beliefs and practices are shared by people in different regions and different religious groups, including those who don’t affiliate with any religion. This report is based on surveys conducted in 36 countries on six continents. The countries have a wide array of religious traditions. Some have Christian, Muslim or Jewish majorities, while others have Hindu or Buddhist majorities. A few are quite religiously mixed, and some have large shares of people who are religiously unaffiliated. Outside the United States, this report draws on nationally representative surveys of 41,503 adults conducted from Jan. 5 to May 22, 2024. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face-to-face in Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ghana, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Tunisia and Turkey. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode, probability-based online panel. For the U.S., data comes from respondents contacted in three separate survey waves in 2023 or 2024: 11,201 respondents were surveyed from July 31 to Aug. 6, 2023, via Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses, which gives nearly all U.S. adults a chance of selection. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. 12,693 respondents were surveyed from Feb. 13 to 25, 2024. Most of the respondents (10,642) in this survey are members of the ATP, and nearly all these panelists also participated in the ATP survey that concluded in Aug. 2023. The remaining U.S. respondents (2,051) in this wave are members of three other panels: the Ipsos KnowledgePanel, the NORC Amerispeak Panel and the SSRS Opinion Panel. All three are national survey panels recruited through random sampling (not “opt-in” polls). We used these additional panels to ensure that the survey would have enough Jewish and Muslim respondents to be able to report on their views. In addition, U.S. data for a few questions comes from 36,908 respondents surveyed from July 17, 2023, to March 4, 2024, as part of the Center’s latest Religious Landscape Study (RLS). This survey was conducted mainly online and on paper, while 3% opted to complete the interview on the telephone. The RLS was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which received support from the Lilly Endowment Inc., Templeton Religion Trust, The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations and the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust. This report was produced by Pew Research Center as part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. Funding for the Global Religious Futures project comes from The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation (grant 63095). This publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Here are the questions and responses used for this report (including information about the U.S. source used for each question), along with the survey methodology. Belief in life after death is widespread around the globe, as is the belief that spirits can reside in animals and in parts of nature such as mountains, rivers or trees, according to a Pew Research Center survey of three dozen countries with a wide range of religious traditions. Moreover, the new survey shows that younger adults are at least as likely as older adults to hold these spiritual beliefs – unlike belief in God, which tends to be more common among older people, globally. Over the last two decades, we’ve conducted surveys about religion and spirituality in more than 100 countries and territories. But in this survey, for the first time, we asked more than 50,000 people across six continents about some beliefs and practices that we previously had explored only in Asia or the United States. This allows us to draw a fuller picture of spirituality around the world. Some of the concepts we asked about have roots in specific religious traditions – such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, or Asian folk religions. Others are associated with less formal religious traditions that some people might label “New Age.” We find that adults around the world – often across religious and geographic boundaries – share many of the beliefs and practices we asked about. For example, majorities of adults in most countries surveyed say that animals can have spirits or spiritual energies. This includes 83% of adults in India, which has a Hindu majority. It also includes 81% in Muslim-majority Turkey, 76% in Christian-majority Argentina and 70% in Israel, the world’s only country with a Jewish majority. Many people around the world also believe that parts of nature (such as mountains, rivers or trees) can have spirits or spiritual energies. This belief is voiced by nearly three-quarters of adults in Christian-majority Chile (74%) and Buddhist-majority Thailand (73%), and by 57% in Muslim-majority Indonesia. The U.S. falls somewhere in the middle of the countries surveyed on these questions: 57% of U.S. adults believe that animals can have spirits, while 48% say the same about mountains, rivers or trees. (Around six-in-ten U.S. adults identify as Christian, and about three-in-ten are religiously unaffiliated.) In general, people around the world are much less likely to say that certain objects (such as crystals, jewels or stones) can have spiritual energies. In some countries where large segments of the population do not identify with any religion, belief in spiritual forces nevertheless is fairly common. In Japan, for example, 53% of adults say that animals can have spirits, and 56% say that parts of nature can have spiritual energies – even

Believing in Spirits and Life After Death Is Common Around the World Read More »