1. International engagement and support for foreign aid

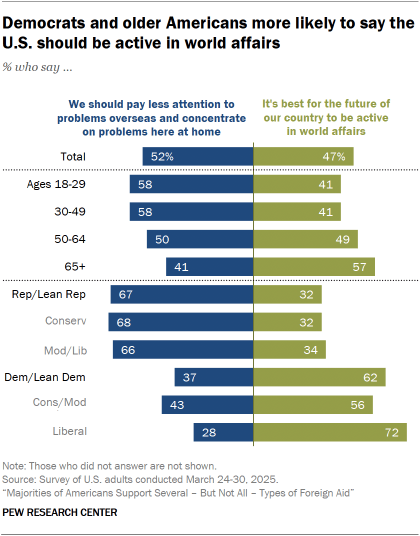

As the U.S. pursues new directions in foreign policy under Trump in his second term, Americans have mixed opinions about how the U.S. should engage with other countries. 47% of U.S. adults say it is best for the future of the country to be active in world affairs. 64% think the U.S. should be willing to compromise with other countries on major international issues. Most Americans say the U.S. should give foreign aid, but support varies widely based on its purpose. Related: Americans Give Early Trump Foreign Policy Actions Mixed or Negative Reviews Should the U.S. be active in world affairs? Just under half of Americans (47%) believe it is best for the future of the country to be active in world affairs. A slightly larger share (52%) say the U.S. should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate on domestic issues. There has been an increase in the share saying it’s best for the country to be active in world affairs since 2024, when 42% of Americans held this view. Views by age, education and party Older Americans are more likely to prefer the U.S. play an active role in world affairs. A majority of those ages 65 and older (57%) take this stance, as do roughly half of those ages 50 to 64. Younger adults are more likely to say the U.S. should concentrate on problems at home, rather than problems overseas. A 58% majority of adults under 50 say this, while 41% prefer the U.S. be active in world affairs. Support for international engagement is higher among Americans with more education: 65% of those with a postgraduate degree say it’s best for the U.S. to be active in world affairs, while 53% of those with a four-year college degree and 41% with some college or less education agree. Roughly six-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents say the U.S. should be active in world affairs, compared with about one-third of Republicans and Republican leaners (32%). This share rises to 72% among Democrats who identify as liberal. For their part, Republicans consistently favor a domestic focus. About two-thirds of Republicans say the U.S. should focus on problems at home, regardless of ideology. Should the U.S. take other countries’ interests into account? Most Americans (64%) say that when dealing with major international issues, the U.S. should take into account the interests of other countries, even if it means making compromises. About a third (34%) say the U.S. should follow its own interests, even when other countries strongly disagree. The share favoring international compromise has increased significantly since 2023, when 59% of Americans held this opinion. Views by party A large majority of Democrats (83%) say the U.S. should take other countries’ interests into account when handling major international issues. This includes 76% of moderate or conservative Democrats and 91% of liberal Democrats. Republicans are more split. Roughly half (52%) say the U.S. should follow its own interests, even when other countries strongly disagree. This share rises to 58% among conservative Republicans. For what reasons should the U.S. give foreign aid? Americans’ support for foreign aid varies depending on its intended purpose. More than three-quarters say that aid should be given to developing countries for medicine and medical supplies (83%) or food and clothing (78%). Smaller majorities support aid for economic development (63%) or for strengthening democracy (61%) in other countries. Fewer Americans approve of aid supporting other countries’ militaries (39%) or art and cultural activities (34%). Related: What the data says about U.S. foreign aid Opinions on foreign aid relate to views of general international engagement: Americans who think the U.S. should be active in world affairs are more likely than those who say the country should focus on domestic issues to support foreign aid for each purpose. Views by party Opinions about foreign aid vary widely by party. Democrats are more supportive than Republicans of every type of foreign aid we asked about. The partisan gap is largest on aid for art and cultural activities in other countries. A 54% majority of Democrats say the U.S. should give this kind of assistance, compared with 15% of Republicans. Democrats are also at least 30 percentage points more likely than Republicans to approve of aid that supports economic development and strengthens democracy. And though partisan gaps still appear, majorities of both Democrats and Republicans say the U.S. should give medicine and medical supplies as well as food and clothing to developing countries. Views by age Older Americans are generally more supportive of giving foreign aid for various reasons. Those ages 50 and older are about 8 points more likely than adults under 50 to say the U.S. should provide aid for medicine and medical supplies, food and clothing, strengthening democracy, and military support. Notably, this pattern flips when it comes to aid for art and cultural activities. Adults under 50 are 10 points more likely than their older counterparts to say the U.S. should give this type of assistance (39% vs. 29%). On foreign aid that supports economic development, adults ages 50 and older and those under 50 express similar support (64% vs. 62%). Views by education Americans with more education, when compared with those who have less, are more supportive of providing most types of foreign aid we asked about. For example, 73% of Americans with a postgraduate degree say the U.S. should give aid to strengthen democracy in other countries, compared with 65% of people whose highest attainment is a four-year college degree. A smaller majority of those with some college or less education (56%) support giving foreign aid to strengthen democracy. There is a very similar pattern on aid for economic development. Almost three-quarters of adults with a postgraduate degree say this is something the U.S. should give, compared with 66% of people with a four-year degree and 60% of people with some college education or less. For most other types of foreign aid asked about, people with at least a four-year degree are more supportive than

1. International engagement and support for foreign aid Read More »