What do religious ‘nones’ believe?

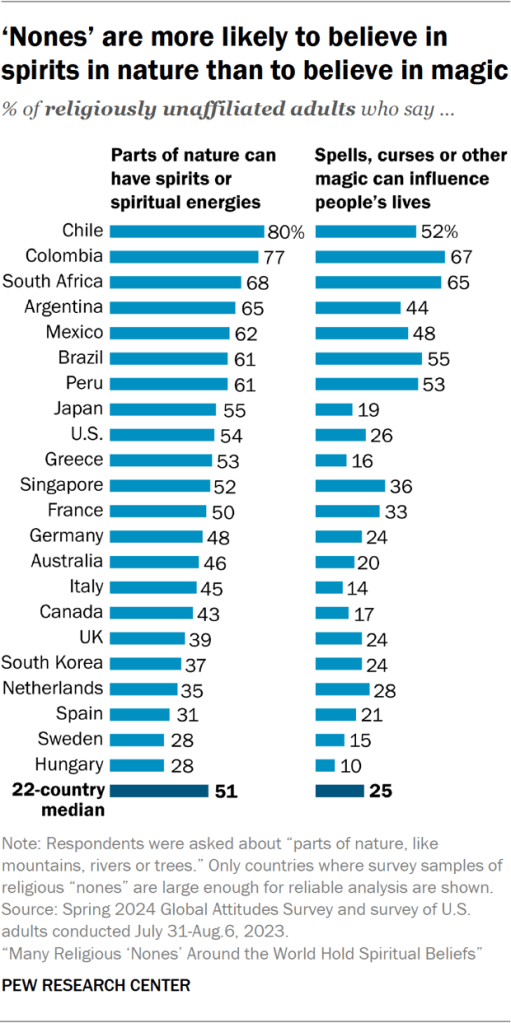

What are religious ‘nones’? “Nones” are adults who describe themselves religiously as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular.” This report uses the terms “nones” and “religiously unaffiliated” interchangeably. Many “nones” express a variety of religious or spiritual beliefs. For example, in many of the 22 countries analyzed by Pew Research Center in this report, sizable shares of “nones” say they believe that something spiritual exists beyond the natural world, and that animals and parts of nature can have spirits or spiritual energies. Belief in an afterlife is also relatively widespread among religiously unaffiliated adults in the countries included in the study. Additionally, in a few countries, majorities of “nones” believe in spells, curses or other magic. And roughly a quarter or more of religiously unaffiliated adults in most of the countries discussed in this report believe that the spirits of ancestors can help or harm them. In one country – South Africa – 81% of “nones” express belief in the power of ancestral spirits. In general, religiously unaffiliated people around the world are less likely to hold religious and spiritual beliefs than are people in the same countries who identify with a religion. For example, “nones” are less likely to believe in God than people who identify with a religion in each of the 22 countries where our survey included enough “nones” for reliable analysis. In Italy, for instance, 16% of “nones” believe in God, compared with 91% of religiously affiliated adults – a difference of 75 percentage points. The differences persist, but are smaller, in countries such as Argentina, where most “nones” (62%) and even higher shares of the religiously affiliated (99%) believe in God. Similar patterns prevail on other beliefs the survey measured. Within the broad category of “nones,” people who identify as atheists generally are less likely than people who describe their religion as “nothing in particular” to hold some spiritual and religious beliefs. For example, in Australia, 14% of atheists say there is life after death, while 37% of people who say their religion is “nothing in particular” believe in an afterlife. Self-described agnostics sometimes are similar to atheists and sometimes differ from them on the wide range of beliefs discussed in this report. We have enough agnostics in our survey samples to provide detailed analyses of their views in only five of the 22 countries surveyed. For country-by-country survey results among agnostics, atheists and people who identify religiously as “nothing in particular,” go to the report topline. Within a country’s population of “nones,” there are often wide gaps in belief between two other subgroups: those who say religion is not at all important in their lives, and those who attribute even a little (or more) personal importance to religion. For example, “nones” who view religion as not at all important are much less likely than other “nones” to say there is definitely or probably an afterlife. The survey findings also indicate that women who are “nones” generally are more likely than men who are “nones” to express a variety of beliefs. Among “nones” in Singapore, for instance, women are about twice as likely as men to believe that spirits can inhabit objects such as crystals, jewels or stones (45% vs. 21%). This pattern is consistent with our previous studies showing that women tend to be more religious than men in many countries, particularly within Christian populations. (The religious and spiritual beliefs of “nones” are also discussed in this report’s Overview.) Belief in God In most of the 22 countries analyzed, at least one-in-five religious “nones” say they believe in God. However, among “nones” who describe their religious identity as “nothing in particular,” the share expressing belief in God varies widely by country. For example, people in the “nothing in particular” category in Latin American countries are a lot more likely than those in European countries to believe in God. One possible explanation for these regional differences is that belief in God is more widespread throughout the general populations (including among religiously affiliated adults) in Latin American countries than in European ones. For instance, nearly universal shares of Christians in all six Latin American countries surveyed express belief in God. Smaller majorities of Christians (about three-quarters) express belief in God in France, Germany and Hungary, while in Sweden, just 58% of self-identified Christians say they believe in God. In general, across the countries with survey samples large enough to enable comparisons between atheists and people who say their religion is “nothing in particular,” atheists are less likely than the “nothing in particular” group to believe in God. For example, in the United Kingdom, 8% of atheists express belief in God, compared with 32% of adults who identify with no particular religion. (Even though atheism is commonly understood to mean not believing in God, small shares of respondents in many places say they are atheists in answer to a religious identification question, yet they say they believe in God or affirm other religious or spiritual beliefs in response to other questions. Some scholars of religion argue that inconsistency or “incongruence” actually is the norm, not the exception, when one looks deeply into the religious identities, beliefs and practices of people around the world.) Belief in ancestral spirits In most of the countries analyzed in this report, about 20% to 40% of religiously unaffiliated adults believe that the spirits of ancestors can help or harm them. This includes 36% of “nones” in France, 31% in Canada and 25% in South Korea. Only in South Africa do a majority of “nones” (81%) believe ancestral spirits can affect them. In general, “nones” who say religion is not at all important in their lives are much less likely than other “nones” to believe that ancestral spirits can help or harm them. For example, in France, 27% of “nones” who say religion is not at all important to them believe in the active role of ancestral spirits, compared with 57% of other “nones.” Self-identified atheists are generally less likely than people

What do religious ‘nones’ believe? Read More »

![[Action required] Your RSS.app Trial has Expired.](https://starthub.asia/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/wp-header-logo-179-300x171.png)