Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking

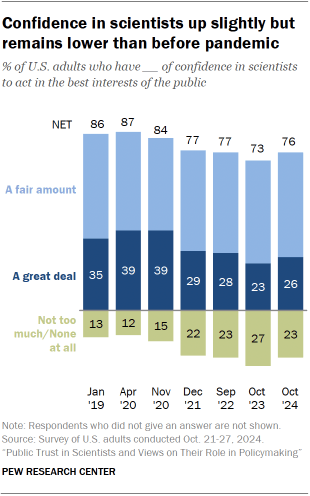

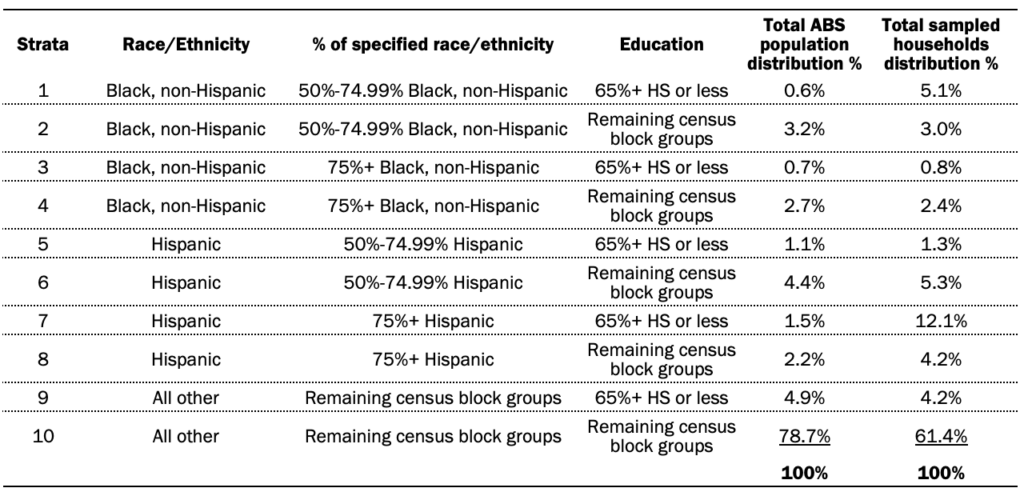

Trust moves slightly higher but remains lower than before the pandemic Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans view scientists and their role in making public policy. For this analysis, we surveyed 9,593 U.S. adults from Oct. 21 to 27, 2024. Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), a group of people recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses who have agreed to take surveys regularly. This kind of recruitment gives nearly all U.S. adults a chance of selection. Surveys were conducted either online or by telephone with a live interviewer. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. Here are the questions used for this report, the topline and the survey methodology. A majority of Americans say they have confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests. Confidence ratings have moved slightly higher in the last year, marking a shift away from the decline in trust seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. A new Pew Research Center survey of 9,593 U.S. adults conducted Oct. 21-27, 2024, takes a close look at the public image of scientists, who serve as one potential source of information for Americans navigating complex policy debates and everyday decisions around things like their personal health and wellness. Key findings 76% of Americans express a great deal or fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests. This is up slightly from 73% in October 2023 and represents a halt to the decline seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientists continue to enjoy strong relative standing compared with the ratings Americans give to many other prominent groups, including elected officials, journalists and business leaders. Majorities view research scientists as intelligent (89%) and focused on solving real-world problems (65%). In addition, about two-thirds (65%) view research scientists as honest and 71% view them as skilled at working in teams. Communication is seen as an area of relative weakness for scientists. Overall, 45% of U.S. adults describe research scientists as good communicators. A slightly larger share (52%) say this phrase does not describe research scientists well. Another critique many Americans hold is the sense that research scientists feel superior to others; 47% say this phrase describes them well. Americans are split over scientists’ role in policymaking. Overall, 51% say scientists should take an active role in public policy debates about scientific issues. By contrast, nearly as many (48%) say they should focus on establishing sound scientific facts and stay out of public policy debates. Americans also aren’t convinced scientists make better policy decisions on science issues than other people – just 43% think this is the case. Democrats continue to express more confidence than Republicans in scientists, but ratings within the GOP have edged higher in the last year. A larger majority of Democrats than Republicans express confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests (88% vs. 66%). Though the partisan gap in trust remains sizable, Republicans’ overall level of confidence in scientists is up 5 percentage points compared with a year ago – the first uptick in trust among Republicans since the start of the pandemic. Partisans also differ over scientists’ role in policy debates, with Democrats far more supportive than Republicans of active engagement in making policy on scientific issues. Trends in trust in scientists In recent years, the scientific community has engaged with the public’s declining trust directly, and there are multiple organizations working on ways to support trust in science and improve communication with wider audiences. About three-quarters of Americans say they have either a great deal (26%) or a fair amount (51%) of confidence in scientists to act in the best interests of the public. This share is up slightly since last year. Still, levels of confidence in scientists remain lower than in April 2020 – at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, 87% expressed at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists, including 39% who said they had a great deal of confidence. Trust in scientists compared with trust in other groups In an era of low public trust in institutions, scientists continue to be held in higher regard than several other prominent groups we’ve asked about, including journalists, elected officials, business leaders and religious leaders. Confidence ratings for scientists are even slightly higher than those for public school principals and police officers – two groups that receive positive overall ratings. Go to the Appendix for more detailed views of these groups. The Appendix also includes views of medical scientists, whose ratings are very similar to those for scientists generally. Differences in confidence by party Roughly nine-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (88%) express a great deal or fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests. The share of Democrats with at least a fair amount of confidence in scientists is similar to levels seen prior to the pandemic. However, the share of Democrats who express a great deal of confidence in scientists stands at 40%, significantly below the peak in strong trust seen during the pandemic’s first year. In April 2020, 52% of Democrats expressed a great deal of confidence in scientists, and in November 2020, that share reached 55%. Republicans’ views follow a different pattern. Two-thirds of Republicans and Republican leaners say they have a great deal or a fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interest. About a third (34%) express distrust, saying they have not too much or no confidence at all in scientists. In April 2020, an 85% majority of Republicans said they had a great deal or fair amount of confidence in scientists, compared with just 14% who had little or no confidence. While GOP ratings of scientists remain much lower than they were before the pandemic, there has been a slight

Public Trust in Scientists and Views on Their Role in Policymaking Read More »