How Americans View Journalists in the Digital Age

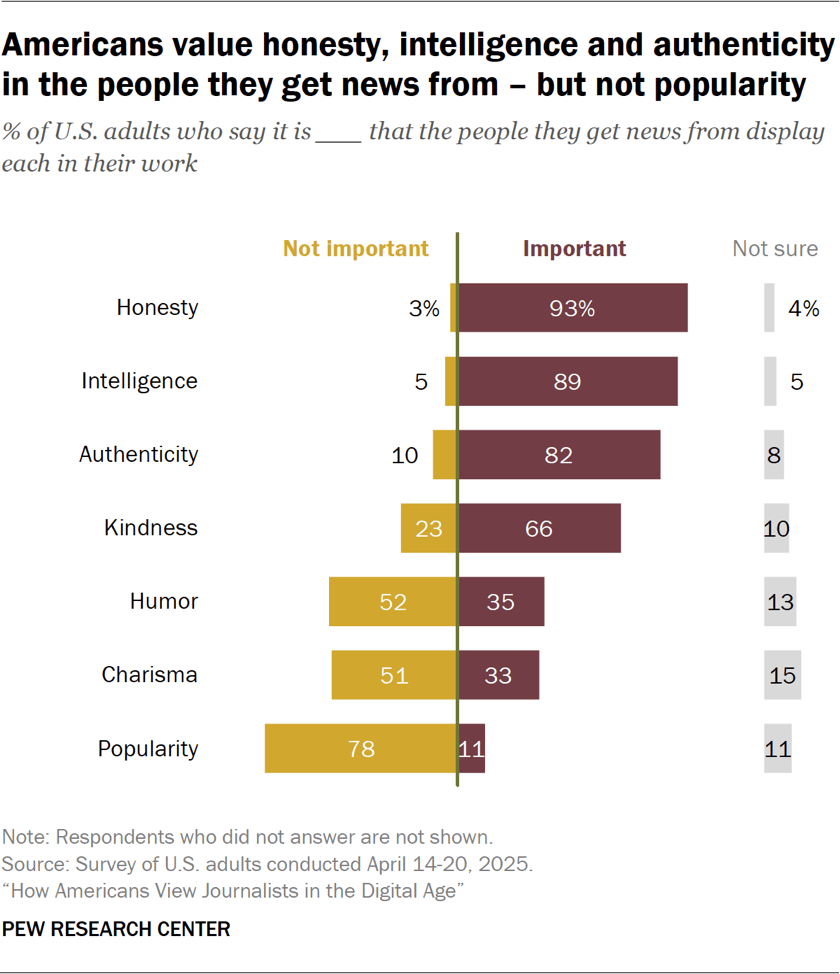

Reporters interview House Majority Leader Steve Scalise, R-La., on his way to the House Chamber at the U.S. Capitol on July 2, 2025. (Kevin Dietsch/Getty Images) How we did this Pew Research Center has been studying how Americans get news and information for many years, and it has become clear that journalists’ place in society has been changing amid major political and technological shifts. So we asked everyday people for their views on this topic, including how they define a “journalist,” how they view journalists’ role in America, and what they want from their news providers more broadly (whether they are journalists or not). We used two different methods to explore Americans’ understandings of what it means to be a journalist in the digital age: Survey We surveyed 9,397 U.S. adults from April 14 to 20, 2025. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), a group of people recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses who have agreed to take surveys regularly. This kind of recruitment gives nearly all U.S. adults a chance of selection. Interviews were conducted either online or by telephone with a live interviewer. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other factors. Read more about the ATP’s methodology. Here are the questions used for this report, the topline and the survey methodology. Focus groups Pew Research Center worked with PSB Insights to conduct nine 90-minute online focus groups with a total of 45 U.S. adults from June 10 to 18, 2025. These discussions are not nationally representative, and the results are not framed in quantitative terms. This report includes findings and quotes from the focus groups to help illustrate and add nuance to the survey findings. Quotes were lightly edited for spelling, punctuation and clarity. To learn more, refer to the methodology. As Americans navigate an often-overwhelming stream of news online – some of it coming from nontraditional news providers – what it means to be a journalist has become increasingly open to interpretation. That is apparent in several ways in a new Pew Research Center study. Who Americans see as a “journalist” depends on both the individual news provider and the news consumer, similar to the variety of ways people define “news.” There is a lack of consensus – and perhaps some uncertainty – about whether someone who primarily compiles other people’s reporting or offers opinions on current events is a journalist, according to a new Center survey. Americans are also split over whether people who share news in “new media” spaces like newsletters, podcasts and social media are journalists. In some ways, Americans’ ideas about journalists are still tied to what the news industry looked like in the 20th century. When asked who comes to mind when they think of a journalist, many everyday Americans who participated in our focus groups said they think of traditional TV newscasters like Walter Cronkite and Tom Brokaw, modern anchors like Lester Holt and Anderson Cooper, and even fictional characters like Clark Kent. Most Americans say journalists are at least somewhat important to the well-being of society. At the same time, many are critical of journalists’ job performance and say they are declining in influence, an opinion that follows years of financial and technological turmoil in the news industry. And many views toward journalists continue to be sharply divided by political party, with Republicans taking a more skeptical view of the profession than Democrats. As part of our broader study of how Americans get news and information nowadays, we wanted to know what people think about the role of journalists in the digital age – including what makes someone a journalist, what Americans think is important for journalists to do in their daily work, and what backgrounds and attributes people are looking for in their news providers broadly (whether they are journalists or not). So earlier this year, we posed these questions in a survey of more than 9,000 Americans and in online focus groups with 45 U.S. adults. Americans want honesty, accuracy and topical knowledge from their news providers What do people want their news providers to be like, regardless of whether they are journalists? Honesty, intelligence and authenticity are the top three traits in our survey that respondents say are important for the people they get news from to display in their work. However, as our focus group discussions illustrate, people hold differing views of what the term “authenticity” means when it comes to news providers – and some aren’t entirely sure. Americans also care more that someone they get news from has deep knowledge of the topics they cover than whether they are employed by a news organization or have a university degree in journalism. Most Americans agree that the people they get news from should definitely report news accurately (84%) and correct false information from public figures (64%) in their daily work. But there is less consensus around several other job functions – and relatively few say their news providers should express personal opinions about current events. Refer to Chapter 1 for more details on what Americans want from their news providers. Who counts as a journalist? Most Americans (79%) agree that someone who writes for a newspaper or news website is a journalist – higher than the share who say the same about someone who reports on TV (65%), radio (59%) or any other medium. There is less consensus about whether people who work in newer media are journalists. Fewer than half of U.S. adults say someone who hosts a news podcast (46%), writes their own newsletter about news (40%) or posts about news on social media (26%) is a journalist. In each of these cases, roughly a quarter of Americans say they aren’t sure whether these people are journalists. This pattern aligns somewhat with how long each format has been around: Newspapers were associated with journalism for centuries

How Americans View Journalists in the Digital Age Read More »

![[Action required] Your RSS.app Trial has Expired.](https://starthub.asia/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/wp-header-logo-179-300x171.png)