3. Views of China in middle-income countries

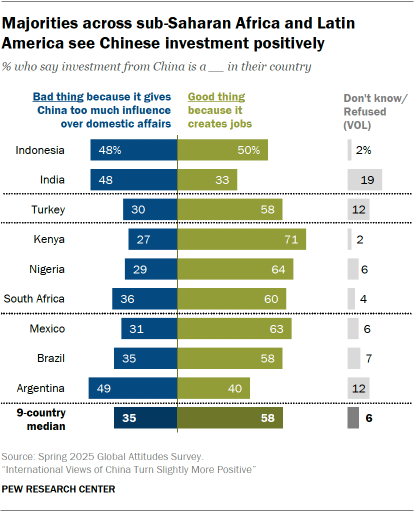

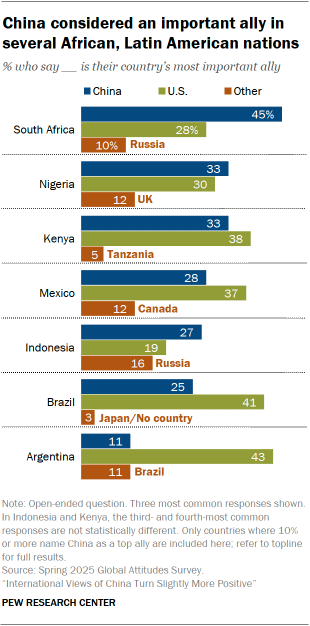

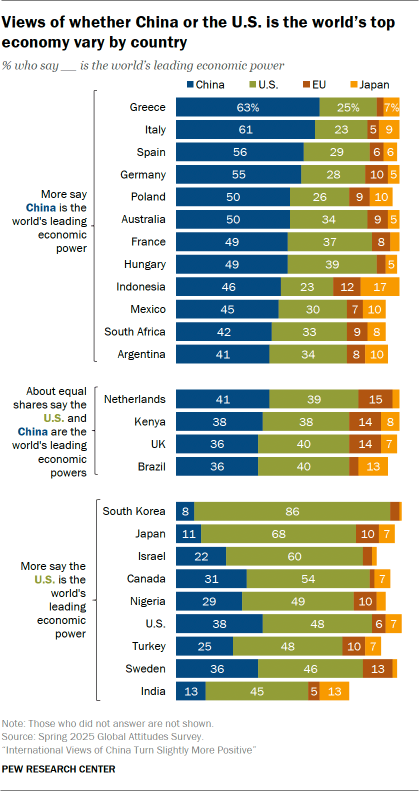

In nine middle-income countries, we asked additional questions about relations with China and the U.S. People in most of the middle-income countries surveyed say investment from China is more of a good thing than a bad thing for their nation. In four countries, people are more likely to describe investment from China as a good thing than to say the same about investment from the U.S. In India, the reverse is true. Out of five specific issues we asked about, people are most likely to describe the debt their country owes to China as a very serious problem. Other problems – including economic competition with China – tend to be seen as less serious for their nation. In most countries and across most issues, people are more likely to describe problems with the U.S. as very serious than to say the same about problems with China, or otherwise view problems with the U.S. and China in a similar light. Views of investment from China Across the nine middle-income nations surveyed, a median of 58% say investment from China is a good thing because it creates jobs in their country. In comparison, a median of 35% say such investment is a bad thing because it gives China too much influence over their domestic affairs. Kenyans are the most positive about investment from China: 71% see it as good for their country. Around six-in-ten adults or more agree in five other countries. Conversely, people in Argentina and India are more likely to describe investment from China as bad than good. Opinions in Indonesia are roughly divided. Views over time Evaluations of investment from China have changed in some countries since the question was last asked in 2019. For example, people in Turkey have become 20 points more likely to say investment from China is good for their country. Views have also turned more positive in Indonesia, Kenya and India. Nigeria stands out as the only country that has soured on investment from China. The share of Nigerians who call it a good thing has declined 18 points since 2019. Comparing views of investment from China and the U.S. People see investment from China more favorably than investment from the U.S. in four of the nine countries where we asked these questions. For instance, Turks are 19 points more likely to say investment from China is good for their country than to say the same about investment from the U.S. Chinese investment also gets higher ratings in Mexico, Indonesia and South Africa. The opposite is true in India, where 33% say investment from China is a good thing, compared with 59% who say the same about investment from the U.S. In four countries, investment from both countries is seen in a similar light. Related: How people in 9 middle-income countries see relations with the U.S., China Views of bilateral issues with China In the middle-income countries surveyed, we also asked about five potential problems that might exist in their relations with China. People were asked whether each issue is very serious, somewhat serious, not too serious or not at all serious. Overall, around half of adults or more tend to say each issue is at least somewhat serious. But far fewer describe each as very serious. (The latter responses are what we analyze here, consistent with our 2022 study based on a similar survey question that was asked in high-income countries.) In five countries, people are most likely to describe the amount of debt their country owes to China as a very serious issue. These include Kenya, Indonesia, Nigeria and Brazil, where six-in-ten adults or more say debt to China is a very serious problem. Overall, a median of 50% across all nine middle-income countries consider debt to China a very serious problem. Aside from debt, no problem is seen as very serious by a majority in any country. In general, only around a third of adults or fewer see each of the other problems as very serious. A median of 35% consider China’s military power to be a very serious problem for their country. The shares describing China’s military power as a very serious issue range from 50% in Brazil to 22% in Mexico. A similar median of 34% consider China’s involvement in their country’s politics to be a very serious problem. This view is most widely held in Indonesia (45%) and Brazil (44%). Conversely, people in Mexico (17%) and Turkey (18%) are the least likely to say China’s involvement in their politics is a very serious problem. A 32% median consider economic competition with China to be a very serious problem. Again, these views are particularly common in Indonesia (49%) and Brazil (46%). China’s human rights policies tend to be one of the issues of least concern in the middle-income countries surveyed, with a median of 28% saying they are a very serious problem. In Brazil, 39% describe China’s human rights policies as a very serious problem, but elsewhere, around a third of adults or fewer take this stance. People in India were additionally asked about China’s territorial disputes with India, which 46% say are a very serious problem. This issue and China’s military power concern Indians the most, labeled very serious problems by around four-in-ten or more. Their views of these territorial disputes are largely unchanged since we first asked this question in 2016: At that time, 45% called them a very serious problem. (Trend data for other countries is not available.) Comparing concerns about China and the U.S. We asked these same questions about the U.S., too, and can compare what problems people see in their country’s relationship with each superpower. In most countries and across most issues, people are more likely to describe problems with the U.S. as very serious than to say the same about problems with China – or otherwise view them in a similar light. For example, more adults in Mexico, South Africa and Turkey say U.S. human rights policies are a very serious problem for their country than say the same about Chinese human rights policies. In Mexico, this gap is particularly sizable at 20 points.

3. Views of China in middle-income countries Read More »

![[Action required] Your RSS.app Trial has Expired.](https://starthub.asia/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/wp-header-logo-179-300x171.png)