2. Views of the Trump administration’s immigration policies

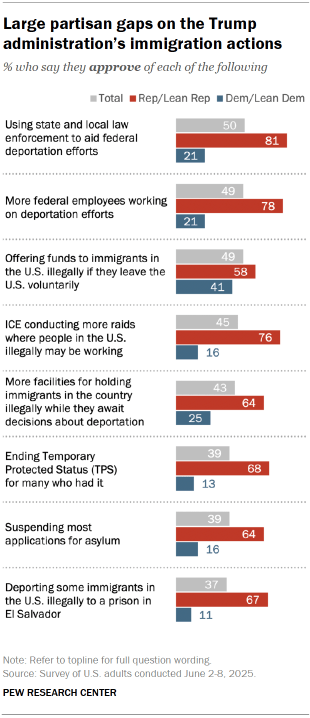

Many Americans disapprove of several of the Trump administration’s most controversial immigration actions. For example, 61% disapprove of deporting some immigrants who are in the United States illegally to a prison in El Salvador, while far fewer – 37% – approve of this policy. Views are similar on suspending asylum applications from people seeking to live in the U.S. There is somewhat more support for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) conducting more raids on workplaces where people in the U.S. illegally may be working. Still, more disapprove (54%) than approve (45%) of increasing these raids. (Note: Most of this survey was conducted before recent protests in Los Angeles and other cities against ICE immigration sweeps and before the Trump administration’s subsequent decision to deploy Marines and National Guard troops to Los Angeles.) The public is roughly split on using state and local law enforcement to aid in deportation efforts and significantly increasing the number of federal employees who are working on such deportation efforts. Notably, substantially expanding the wall along the U.S. border with Mexico – a signature policy priority of Donald Trump’s first term – draws majority support. Currently, 56% favor expanding the border wall, up from 46% in 2019. Wide partisan gaps in approval of Trump’s immigration policies Republicans largely approve of all eight administration policies included in the survey, while majorities of Democrats disapprove of each policy. Still, opinions among partisans vary across the individual items. Among Republicans Sizable majorities of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents support expanding enforcement efforts against people in the U.S. illegally: 81% approve of using state and local law enforcement to help with efforts to deport those in the U.S. illegally. 78% approve of increasing the number of federal employees devoted to deportation efforts. 76% approve of increased workplace raids by ICE. There is somewhat less GOP support for other actions. About six-in-ten Republicans (58%) approve of offering money and travel funds to immigrants in the U.S. illegally if they voluntarily leave – the lowest of any item included on the survey. Among Democrats For seven of the eight Trump administration immigration policies asked about in the survey, no more than a quarter of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents approve. The policy that draws the most support among Democrats is the approach that attracts the least support among Republicans: 41% of Democrats approve of offering money and travel funds to immigrants in the U.S. illegally if they voluntarily leave the country. Views by race, ethnicity and party Opinions about the administration’s immigration policies vary by race and ethnicity. But there are wider differences by race and ethnicity among Republicans than Democrats. Race and ethnicity Hispanic and Black Americans are deeply skeptical of the administration’s immigration policies: Fewer than four-in-ten Hispanic Americans approve of seven out of the eight policies included in the survey. A larger share (45%) approve of offering money and travel funds to people in the U.S. illegally to leave the country voluntarily. No more than about a third of Black adults approve of any of these immigration policies. Opinions among Asian Americans vary widely across the policies: Majorities approve of using state and local law enforcement to help with deportation efforts (58%) and offering funds to those here illegally who self-deport (59%). But there is far less support for other policies. Majorities of White adults approve of several of the administration’s policies. For instance, 59% support using state and local law enforcement to help with deportation efforts, and 56% approve of increasing the number of federal employees working on efforts to detain and deport people in the U.S. illegally. Race and ethnicity among partisans There are substantial differences among Republicans by race and ethnicity on these questions, with White Republicans more likely than Hispanic Republicans to approve of most of these policies. For example, most White Republicans (87%) approve of using state and local law enforcement to help with efforts to deport people in the country illegally. A much smaller share (57%) of Hispanic Republicans share this view. There are similar gaps between White and Hispanic Republicans on increasing the number of federal employees working on efforts to detain and deport people in the U.S. illegally (84% vs. 55%) and ICE conducting more raids where people in the U.S. illegally may be working (82% vs. 58%). Racial and ethnic differences in views of Trump policies are much narrower among Democrats. Age differences in views of Trump’s immigration policies For the most part, Trump’s immigration actions draw more support among people 50 and older than among younger adults. Nearly six-in-ten older adults approve of using state and local law enforcement to aid deportation efforts (58%) and of increasing federal personnel working on these efforts (57%). By comparison, about four-in-ten adults under 50 approve each of these policies. Age differences in attitudes about immigration policies are particularly pronounced among Republicans. For example, while 89% of Republicans ages 50 and older approve of using state and local law enforcement to help with efforts to deport people in the U.S. illegally, a smaller majority (73%) of those under 50 say the same. And older Republicans are more likely than younger Republicans to say they approve of ICE conducting more raids where people in the U.S. illegally may be working (85% vs. 67%). The pattern of older Republicans being more likely than younger Republicans to approve of the administration’s immigration approach is consistent across all of these policies. Expanding the wall along the U.S. border with Mexico A narrow majority of Americans (56%) favor substantially expanding the wall along the U.S.-Mexico border – a 10 percentage point increase from 2019. This increased support is largely driven by shifts among Democrats. Most Democrats continue to oppose substantially expanding the border wall (73%). But Democrats are about twice as likely to favor expansion today (27%) than they were in 2019 (14%). 36% of conservative and moderate Democrats favor expansion today, up from 19% in 2019. 14% of liberal Democrats favor expanding the wall, up from 9%

2. Views of the Trump administration’s immigration policies Read More »